01dragonslayer

Iron Killer

Mad Referrer

Jacked Immortal

EG Auction Sniper

VIP Member

Shout Master

Mutated

Fully Loaded

- EG Cash

- 1,113,688

Hey, remember when we used to believe if we didn’t eat “six small meals a day” we’d somehow damage our metabolism, turn into a big ball of adipose tissue and then, I dunno, spontaneously combust or something? Fun times.

Fortunately for us––and I guess the environment––research showed this wasn’t really true and meal frequency wasn’t as big a deal as once believed. 1 Then, the pendulum began to swing, and we went from eating frequently to skipping meals entirely as fasting diets became the new cool thing.

While there are dozens of ways to implement a fast, the most popular approach is what we refer to as “intermittent fasting” or IF (formally referred to as “time-restricted eating” in the literature) due to its simplicity and ease of implementation: You don’t eat for a few hours, followed by a period of eating. For example, the 16:8 approach, where you fast for 16 hours and eat for 8 hours.

The popularity of this style of fasting has extended beyond the mainstream and into the research world, with several studies having been published on this particular style of fasting over the years.

On the whole, studies suggest when intermittent fasting is implemented without calorie restriction, participants tend to lose a little bit of weight owing to a spontaneous reduction in calorie intake. But when calories are controlled, there doesn’t appear to be an advantage to fasting. In other words, the so-called “magic” of fasting is really just a result of inadvertently creating an energy deficit.

However, most of these studies have been fairly short term (ranging from 4 days to 12 weeks) with a relatively small number of participants (8-80). 2 It could be the case that if these studies took place over a longer timeframe with more participants, there may be an advantage to fasting that isn’t apparent from shorter-term trials.

Well, a recent study by Liu et al. (2022) might hold the answer. The researchers conducted a 12-month randomized clinical trial to assess time-restricted eating with calorie restriction compared with daily calorie restriction alone for the effects on weight loss and metabolic risk factors in obese patients.

Let’s see what they found.

All participants received dietary counselling by trained health coaches. During the first 6 months of the study, they were encouraged to weigh and log foods alongside taking photographs of their meals. During the second 6 months of the study, participants were instructed to maintain their diet regimens but were only required to fill out their food logs and photograph their meals 3 days per week.

The primary study outcome was the change from baseline in body weight at 12 months.

The secondary outcomes included changes in waist circumference, body fat, lean mass, and metabolic risk factors, including levels of plasma glucose, insulin sensitivity, serum lipids, and blood pressure.

Of the 139 participants who started the study, 135 participants (97.1%) completed the first 6 months and 118 participants (84.9%) completed the entire 12 months.

The mean percentage of days that participants adhered to both the calorie intake and eating period was 84.0% in the time-restricted eating group and 83.8% in the daily calorie restriction group.

Weight Loss

There was no significant difference between the two groups in weight change (net difference, −1.8 kg [−4.0 to 0.4]).

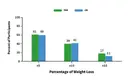

The percentage of participants with a weight loss of more than 5%, 10%, and 15% at 12 months were similar in the two groups.

Additionally, participants in both groups had similar reductions from baseline in waist circumference and BMI.

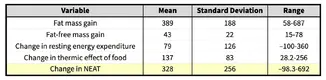

Body Composition

Both groups lost body fat with no significant difference between them (net difference, −1.5kg [−3.1 to 0.2]).

Both groups also lost lean mass, visceral, subcutaneous, and liver fat with no differences between groups.

Blood Pressure, Lipids, Glucose, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

Both interventions were associated with reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure over 12 months, with no substantial between-group differences. Nor were there between-group differences in fasting glucose levels, 2-hour postprandial glucose levels, scores on the insulin disposition index and HOMA–IR, and lipid levels.

Adverse Events

No deaths or serious adverse events were reported during the trial.

A 2018 meta-analysis (that is, a study of the studies), for instance, compared intermittent fasting diets to continuous calorie restriction. Eleven studies were included in the final analysis, ranging from 8-24 weeks in duration. Both diets led to a comparable weight loss of -0.61 kg and percentage weight loss of -0.38%. 3

Headland et al. (2019) conducted a 12-month randomised controlled trial to investigate the effect of fasting vs. continuous energy restriction on weight loss in healthy overweight or obese adults. 4

Participants were split into three different groups:

But what about the muscle loss reported in this study––could an intermittent fasting diet be detrimental to muscle retention during a fat loss diet?

I don’t think so. In the present study, protein intake was way below the recommended intake (on average, it worked out to about 0.3g/lb versus the recommended 0.7g/lb). Furthermore, while the participants were instructed to continue their normal exercise plan, there wasn’t any indication of what exactly this consisted of, so we can’t say whether or not they were engaging in structured resistance training.

Thankfully, we do have other research that’s looked at time-restricted eating and its impact on muscle retention.

A 2019 study investigated the effects of time-restricted feeding in a group of active women who were placed in a small deficit while resistance training 3x/week and consuming 1.6g/kg (0.7g/lb) of protein. The researchers found that time-restricted feeding “did not attenuate RT adaptations in resistance-trained females.” 9

A year later, Stratton and colleagues conducted another study pitting time-restricted feeding against continuous calorie restriction. Both groups were in a 25% caloric deficit (similar to the deficit seen in the study under review), consuming 1.8g/kg (0.8g/lb) of protein, and resistance training 3x/week. After 4 weeks, both groups lost body fat and maintained their lean mass. 10

Moro et al. (2021) conducted a 12-month study comparing time-restricted feeding to a continuous calorie deficit and also reported no muscle loss despite the participants in the fasting group ending up in deficit. Nor did they experience any strength losses when compared to the control group. 11

All told, as long as you establish a sensible deficit, eat enough protein, and continue resistance training, following an intermittent fasting diet isn’t likely to cause muscle or strength loss.

In sum: This 12-month study found no difference in weight loss when comparing time-restricted feeding to daily calorie restriction when both groups were in a similar deficit. Both dieting interventions also produced similar effects with respect to reductions in body fat, visceral fat, blood pressure, glucose levels, and lipid levels over the 12-months.

Before wrapping up, I want to point out that the results of this study don’t suggest “fasting is pointless” or “doesn’t work” as some mainstream news outlets were quick to declare when this study was published. Rather, fasting can be another tool to get the job done. Some people (myself included) prefer fasting. Others may not. This is good news, it means you can pick and choose a style of eating that works for you and your lifestyle.

Fortunately for us––and I guess the environment––research showed this wasn’t really true and meal frequency wasn’t as big a deal as once believed. 1 Then, the pendulum began to swing, and we went from eating frequently to skipping meals entirely as fasting diets became the new cool thing.

While there are dozens of ways to implement a fast, the most popular approach is what we refer to as “intermittent fasting” or IF (formally referred to as “time-restricted eating” in the literature) due to its simplicity and ease of implementation: You don’t eat for a few hours, followed by a period of eating. For example, the 16:8 approach, where you fast for 16 hours and eat for 8 hours.

The popularity of this style of fasting has extended beyond the mainstream and into the research world, with several studies having been published on this particular style of fasting over the years.

On the whole, studies suggest when intermittent fasting is implemented without calorie restriction, participants tend to lose a little bit of weight owing to a spontaneous reduction in calorie intake. But when calories are controlled, there doesn’t appear to be an advantage to fasting. In other words, the so-called “magic” of fasting is really just a result of inadvertently creating an energy deficit.

However, most of these studies have been fairly short term (ranging from 4 days to 12 weeks) with a relatively small number of participants (8-80). 2 It could be the case that if these studies took place over a longer timeframe with more participants, there may be an advantage to fasting that isn’t apparent from shorter-term trials.

Well, a recent study by Liu et al. (2022) might hold the answer. The researchers conducted a 12-month randomized clinical trial to assess time-restricted eating with calorie restriction compared with daily calorie restriction alone for the effects on weight loss and metabolic risk factors in obese patients.

Let’s see what they found.

What did the researchers do?

The study took place in China and 139 participants with obesity (71 men, 68 women) were randomly assigned to one of two groups for a 12-month period.- Time-restricted eating (n=69). Participants consumed the prescribed calorie intake within an 8-hour window (from 8 am to 4 pm) every day. Only non-caloric beverages were permitted during the fasting window.

- Daily calorie restriction (n=70). Participants could consume the prescribed calorie intake without any time restrictions.

All participants received dietary counselling by trained health coaches. During the first 6 months of the study, they were encouraged to weigh and log foods alongside taking photographs of their meals. During the second 6 months of the study, participants were instructed to maintain their diet regimens but were only required to fill out their food logs and photograph their meals 3 days per week.

The primary study outcome was the change from baseline in body weight at 12 months.

The secondary outcomes included changes in waist circumference, body fat, lean mass, and metabolic risk factors, including levels of plasma glucose, insulin sensitivity, serum lipids, and blood pressure.

What did the researchers find?

Adherence and calorie intakeOf the 139 participants who started the study, 135 participants (97.1%) completed the first 6 months and 118 participants (84.9%) completed the entire 12 months.

The mean percentage of days that participants adhered to both the calorie intake and eating period was 84.0% in the time-restricted eating group and 83.8% in the daily calorie restriction group.

Weight Loss

There was no significant difference between the two groups in weight change (net difference, −1.8 kg [−4.0 to 0.4]).

The percentage of participants with a weight loss of more than 5%, 10%, and 15% at 12 months were similar in the two groups.

Additionally, participants in both groups had similar reductions from baseline in waist circumference and BMI.

Body Composition

Both groups lost body fat with no significant difference between them (net difference, −1.5kg [−3.1 to 0.2]).

Both groups also lost lean mass, visceral, subcutaneous, and liver fat with no differences between groups.

Blood Pressure, Lipids, Glucose, and Cardiometabolic Risk Factors

Both interventions were associated with reduced systolic and diastolic blood pressure over 12 months, with no substantial between-group differences. Nor were there between-group differences in fasting glucose levels, 2-hour postprandial glucose levels, scores on the insulin disposition index and HOMA–IR, and lipid levels.

Adverse Events

No deaths or serious adverse events were reported during the trial.

Practical applications

This is another study that adds to the body of research showing that once calories are controlled for, fasting diets don’t have a weight-loss advantage over continuous calorie restriction.A 2018 meta-analysis (that is, a study of the studies), for instance, compared intermittent fasting diets to continuous calorie restriction. Eleven studies were included in the final analysis, ranging from 8-24 weeks in duration. Both diets led to a comparable weight loss of -0.61 kg and percentage weight loss of -0.38%. 3

Headland et al. (2019) conducted a 12-month randomised controlled trial to investigate the effect of fasting vs. continuous energy restriction on weight loss in healthy overweight or obese adults. 4

Participants were split into three different groups:

- Continuous energy restriction (1000 kcal/day for women and 1200 kcal/day for men).

- Week-on-week-off energy restriction (alternating between the same energy restriction as the continuous group for one week and one week of habitual diet).

- or 5:2 (500 kcal/day on modified fast days each week for women and 600 kcal/day for men).

- Continuous energy restriction: −6.6 kg

- Week-on, week-off: −5.1 kg

- 5:2 group: −5.0 kg

- Continuous: −4.5 kg

- Week-on-week-off: −2.8 kg

- 5:2: −3.5 kg

In the presently reviewed study, both groups also saw improvements in all their health markers. Again, a finding that’s in line with the research as a whole that the health benefits fasting advocates latch on to is really just a result of losing excess body fat, which, yep you guessed it, is a result of creating a calorie deficit. Sorry folks, no magic. 6 7 8We found that intermittent fasting may help people to lose more weight than ‘eating as usual’ (not dieting) but was similar to energy restriction diets.

But what about the muscle loss reported in this study––could an intermittent fasting diet be detrimental to muscle retention during a fat loss diet?

I don’t think so. In the present study, protein intake was way below the recommended intake (on average, it worked out to about 0.3g/lb versus the recommended 0.7g/lb). Furthermore, while the participants were instructed to continue their normal exercise plan, there wasn’t any indication of what exactly this consisted of, so we can’t say whether or not they were engaging in structured resistance training.

Thankfully, we do have other research that’s looked at time-restricted eating and its impact on muscle retention.

A 2019 study investigated the effects of time-restricted feeding in a group of active women who were placed in a small deficit while resistance training 3x/week and consuming 1.6g/kg (0.7g/lb) of protein. The researchers found that time-restricted feeding “did not attenuate RT adaptations in resistance-trained females.” 9

A year later, Stratton and colleagues conducted another study pitting time-restricted feeding against continuous calorie restriction. Both groups were in a 25% caloric deficit (similar to the deficit seen in the study under review), consuming 1.8g/kg (0.8g/lb) of protein, and resistance training 3x/week. After 4 weeks, both groups lost body fat and maintained their lean mass. 10

Moro et al. (2021) conducted a 12-month study comparing time-restricted feeding to a continuous calorie deficit and also reported no muscle loss despite the participants in the fasting group ending up in deficit. Nor did they experience any strength losses when compared to the control group. 11

All told, as long as you establish a sensible deficit, eat enough protein, and continue resistance training, following an intermittent fasting diet isn’t likely to cause muscle or strength loss.

In sum: This 12-month study found no difference in weight loss when comparing time-restricted feeding to daily calorie restriction when both groups were in a similar deficit. Both dieting interventions also produced similar effects with respect to reductions in body fat, visceral fat, blood pressure, glucose levels, and lipid levels over the 12-months.

Before wrapping up, I want to point out that the results of this study don’t suggest “fasting is pointless” or “doesn’t work” as some mainstream news outlets were quick to declare when this study was published. Rather, fasting can be another tool to get the job done. Some people (myself included) prefer fasting. Others may not. This is good news, it means you can pick and choose a style of eating that works for you and your lifestyle.