01dragonslayer

Iron Killer

Mad Referrer

Jacked Immortal

EG Auction Sniper

VIP Member

Shout Master

Mutated

Fully Loaded

- EG Cash

- 1,113,688

Reverse dieting is an idea that’s become popular over the last few years. Most of you reading this have probably heard the term but just in case you haven’t, here’s a quick recap: At the end of an extended diet, you gradually increase calories via carbs and fats to ‘reverse’ out of the deficit and back to maintenance. Emphasis on ‘gradually’ because the increase in calories is painfully small to the tune of 50-100kcal per week.

This slow increase in food intake prevents fat regain and reputedly helps ‘repair’ the damage caused to your metabolism during the diet. Not just that, but it can also increase your metabolic capacity to a point where you’re eating more calories than you were previously, all while maintaining low levels of body fat.

Sounds great, right? Almost magical. Unfortunately, the claims don’t hold up.

So the question begging to be asked is: If we know returning to maintenance abates metabolic adaptations during a deficit, why would you spend more time in a deficit versus returning to maintenance as quickly as possible?

Well, don’t look at me because I sure as hell don’t know.

But, unfortunately, you can’t change your basal metabolic rate. For instance, short-term overfeeding studies that fed participants thousands of calories above their maintenance report only a transient increase in metabolic rate between 3-10%, returning to baseline within 24 hours. The majority of this increase, by the way, is due to the thermic effect of food; the calories your body burns digesting food. 1 2 3

Think about that: People’s metabolic rate doesn’t change even when they’re overfed thousands of calories, so do you really think adding 50-100kcal every week is going to do anything for your metabolism?

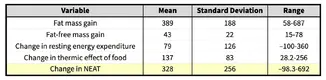

Indeed, you’ll see an increase in metabolic rate as you transition from a deficit back to maintenance, but this increase is largely due to an increase in energy expenditure—notably, an increase in NEAT and improved gym performance. For instance, the table below is taken from a study that found after 8 weeks of overfeeding participants 1000kcal/day, total energy expenditure increased wholly due to the increase in NEAT.

Source

Source

For example, one gram of carbohydrate comes with 3g of water. Let’s assume at the end of your diet you were eating 100g of carbs per day. You end your diet and increase carbs to 200g which is accompanied by 600g of water. This could be an increase of up to ~1.3 lbs on the scale.

Further, the stomach can hold up to 4 litres of food and liquid. Of course, you aren’t going to be eating until you pop, so for the sake of this example let’s say you increase calories to maintenance which amounts to ~2 litres of food and liquid. This could show an increase of up to ~4lbs on the scale.

If we add the ~1.3lb increase from carbs and water, that’s a total of a ~5lb increase on the scale. But this ‘gain’ isn’t fat, it’s just a fluctuation due to the reasons above, and it’ll stabilise within a week of eating at maintenance.

Reverse dieting in the typical fashion (adding a minuscule amount of calories back into the diet) avoids the abrupt spike in scale weight which can seem like you’re eating more food without gaining fat. But in reality, you’ve increased calories by such a small amount the increase isn’t reflected on the scale.

Oh, and not forgetting the fact you’re, uh, you know, still in a deficit. And because the body can’t create fat cells out of thin air, you’re maintaining leanness because you’re still eating fewer calories than your body needs.

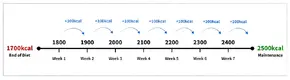

Here’s a hypothetical example to help illustrate this. Let’s assume you end your diet at 1700 kcals, and your maintenance intake is 2500 kcal. You add 100 kcals back to your diet every week until you finally reach maintenance.

As you can see from the image above, despite adding 100kcal to your diet every week, you’re still in a deficit. Not only that but it’s taken an additional eight weeks on top of however long you were dieting to reach maintenance. If you added 50 kcals per week, you could double this time frame to almost 3 months of additional dieting. I don’t know about you, but if I’ve just spent months in a deficit, the last thing I want to do is to extend the diet for several more weeks for absolutely no reason at all.

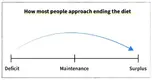

Most people go from eating in a deficit right back to how they were eating before the diet, which is almost always a calorie surplus. So yeah, no shit you gained all the weight back. But this has nothing to do with a “damaged metabolism”, but a discrepancy in your calorie intake.

As you diet and get leaner, the number of calories you need to maintain your new weight decreases. (I’ve discussed this in detail here.) So at the end of a diet, you need to find your “new maintenance”.

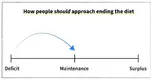

Thankfully, there’s a far more sensible way to end the diet so you can start eating more calories right away, maintain your progress, and avoid large fluctuations in scale weight.

For example, let’s say at the start of the diet your maintenance intake was ~2400 kcals. After a few months of dieting, you’ve lost a lot of weight and your new maintenance is ~2200 kcals.

At the end of the diet, you were eating ~1700 kcals. So, the difference between your current intake and your new maintenance is 500 kcals. Meaning, you’ll need to add 500 kcals to your current intake to return to maintenance.

→ 1700 (current intake) – 2200 (new maintenance) = 500 kcals

Once you’ve calculated the difference, split this amount in half and add 50% to your current intake in week 1 and the remaining 50% in week 2. So using the example above, you’d add 250 kcals to your current intake right away and 250 kcals the week after.

→ Calories required to return to maintenance = 500 kcals

→ Week 1: 1700 + 250 = 1950 kcals

→ Week 2: 1950 + 250 = 2200 kcals

This slow increase in food intake prevents fat regain and reputedly helps ‘repair’ the damage caused to your metabolism during the diet. Not just that, but it can also increase your metabolic capacity to a point where you’re eating more calories than you were previously, all while maintaining low levels of body fat.

Sounds great, right? Almost magical. Unfortunately, the claims don’t hold up.

Claim #1: Reverse dieting can fix your metabolism

This idea that you can somehow damage your metabolism which then requires a special nutrition plan or supplement to fix is a myth. (A myth I’ve discussed here and here.) There is some downregulation of the metabolic rate when dieting (known as metabolic adaptation), but this dissipates once you return to maintenance.So the question begging to be asked is: If we know returning to maintenance abates metabolic adaptations during a deficit, why would you spend more time in a deficit versus returning to maintenance as quickly as possible?

Well, don’t look at me because I sure as hell don’t know.

Claim #2: Reverse dieting can increase your metabolic capacity

Reverse dieting evangelists will claim that by very slowly increasing calorie intake, you’ll be able to increase your metabolic rate to a point where you’re eating more food than you were during the diet (and even before that) all while maintaining a lean physique.But, unfortunately, you can’t change your basal metabolic rate. For instance, short-term overfeeding studies that fed participants thousands of calories above their maintenance report only a transient increase in metabolic rate between 3-10%, returning to baseline within 24 hours. The majority of this increase, by the way, is due to the thermic effect of food; the calories your body burns digesting food. 1 2 3

Think about that: People’s metabolic rate doesn’t change even when they’re overfed thousands of calories, so do you really think adding 50-100kcal every week is going to do anything for your metabolism?

Indeed, you’ll see an increase in metabolic rate as you transition from a deficit back to maintenance, but this increase is largely due to an increase in energy expenditure—notably, an increase in NEAT and improved gym performance. For instance, the table below is taken from a study that found after 8 weeks of overfeeding participants 1000kcal/day, total energy expenditure increased wholly due to the increase in NEAT.

Source

SourceClaim #3: Reverse dieting can minimise fat gain

As you introduce more food back into your diet, your weight will increase for two reasons: You have more food in your stomach, and there’s an increase in muscle glycogen and water.

For example, one gram of carbohydrate comes with 3g of water. Let’s assume at the end of your diet you were eating 100g of carbs per day. You end your diet and increase carbs to 200g which is accompanied by 600g of water. This could be an increase of up to ~1.3 lbs on the scale.

Further, the stomach can hold up to 4 litres of food and liquid. Of course, you aren’t going to be eating until you pop, so for the sake of this example let’s say you increase calories to maintenance which amounts to ~2 litres of food and liquid. This could show an increase of up to ~4lbs on the scale.

If we add the ~1.3lb increase from carbs and water, that’s a total of a ~5lb increase on the scale. But this ‘gain’ isn’t fat, it’s just a fluctuation due to the reasons above, and it’ll stabilise within a week of eating at maintenance.

Reverse dieting in the typical fashion (adding a minuscule amount of calories back into the diet) avoids the abrupt spike in scale weight which can seem like you’re eating more food without gaining fat. But in reality, you’ve increased calories by such a small amount the increase isn’t reflected on the scale.

Oh, and not forgetting the fact you’re, uh, you know, still in a deficit. And because the body can’t create fat cells out of thin air, you’re maintaining leanness because you’re still eating fewer calories than your body needs.

Here’s a hypothetical example to help illustrate this. Let’s assume you end your diet at 1700 kcals, and your maintenance intake is 2500 kcal. You add 100 kcals back to your diet every week until you finally reach maintenance.

As you can see from the image above, despite adding 100kcal to your diet every week, you’re still in a deficit. Not only that but it’s taken an additional eight weeks on top of however long you were dieting to reach maintenance. If you added 50 kcals per week, you could double this time frame to almost 3 months of additional dieting. I don’t know about you, but if I’ve just spent months in a deficit, the last thing I want to do is to extend the diet for several more weeks for absolutely no reason at all.

This doesn’t mean reverse dieting’s entirely pointless

While it can seem like I’m shitting on reverse dieting (well ok, I am, but only the bastardised version that’s become so prevalent in the fitness mainstream), I’d be remiss not to mention the popularity of reverse dieting has had one benefit: It’s raised awareness around the importance of ending a diet properly, so you don’t lose the progress you’ve made and/or end up rebounding.Most people go from eating in a deficit right back to how they were eating before the diet, which is almost always a calorie surplus. So yeah, no shit you gained all the weight back. But this has nothing to do with a “damaged metabolism”, but a discrepancy in your calorie intake.

As you diet and get leaner, the number of calories you need to maintain your new weight decreases. (I’ve discussed this in detail here.) So at the end of a diet, you need to find your “new maintenance”.

Thankfully, there’s a far more sensible way to end the diet so you can start eating more calories right away, maintain your progress, and avoid large fluctuations in scale weight.

Enter the “transition diet”

The “transition diet” is my take on reverse dieting. And as the name suggests, it’s when you transition from the deficit to maintenance. But unlike typical reverse dieting that has you adding back 50-100 kcal every week, the transition diet introduces calories faster, to get you out of the deficit as soon as possible.

How to do it

The transition diet involves calculating your current maintenance (based on your new body weight). Then you work out the difference between how many calories you’re eating right now (i.e., the end of the diet) and your new maintenance intake. (Don’t overthink this: Just use any TDEE calculator to find your new maintenance intake and stick with it.)For example, let’s say at the start of the diet your maintenance intake was ~2400 kcals. After a few months of dieting, you’ve lost a lot of weight and your new maintenance is ~2200 kcals.

At the end of the diet, you were eating ~1700 kcals. So, the difference between your current intake and your new maintenance is 500 kcals. Meaning, you’ll need to add 500 kcals to your current intake to return to maintenance.

→ 1700 (current intake) – 2200 (new maintenance) = 500 kcals

Once you’ve calculated the difference, split this amount in half and add 50% to your current intake in week 1 and the remaining 50% in week 2. So using the example above, you’d add 250 kcals to your current intake right away and 250 kcals the week after.

→ Calories required to return to maintenance = 500 kcals

→ Week 1: 1700 + 250 = 1950 kcals

→ Week 2: 1950 + 250 = 2200 kcals

Why split the intake?

Two reasons:- The slower increase in calories helps minimise large fluctuations on the scale that can mess with people’s heads.

- Everyone differs in their response to a deficit. Some people experience a larger reduction in energy expenditure at the end of a diet compared to others. Adding back calories over two weeks can help ensure you don’t “overshoot” maintenance.