01dragonslayer

Iron Killer

Mad Referrer

Jacked Immortal

EG Auction Sniper

VIP Member

Shout Master

Mutated

Fully Loaded

- EG Cash

- 1,113,688

By Aadam | Last Updated: July 7th, 2022

This post is taken from the Vitamin. Every Thursday, I drop some knowledge bombs on your face to help you reach your goals faster while avoiding all the bullshit.

We get so caught up in trying to find the “perfect” nutrition, training, or supplement plan that we forget some of the most effective things we can do for our health and body composition are also the simplest.

One of these things is getting enough sleep.

For starters, chronic sleep loss can have a multitude of undesirable effects on the cardiorespiratory, nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, and increase the risk of injury and illness. 1

At the broad population level, there’s an association between those with a ‘restricted’ habitual sleep pattern (less than 7hrs per night) and an increased body mass index when compared to those who have a longer habitual sleep pattern (7 hrs or greater per night). 2

There’s also emerging evidence suggesting sleep restriction causes increased energy intake.

A 2017 review reported that, compared to participants who slept ~7 hours per night, participants who slept less than 5 hours per night consumed 385 more calories per day, with more of the calories coming from an increase in fat intake. 3

Zhu et al. found sleep restriction increased subjective hunger, and the sleep-deprived participants consumed ~250 more calories per day than the participants who got enough sleep. But that wasn’t all. The sleep restriction group also gained more weight, saw a decrease in insulin sensitivity, and changes in brain activity–particularly those regions related to cognitive control and reward. 4

And more recently, a review by Fenton et al. found that sleep duration restricted to <5.5 hours per night led to a mean increase of 204kcal/d. 5

But let’s back up for a sec. Why would less sleep affect energy intake in the first place? There are several potential mechanisms, and I’ve married together the rationale from two reviews. 6 7

For starters, being awake for longer means there’s more opportunity to eat, and when you’re awake and sleep-restricted, a food stimulus has been demonstrated to enhance the activation of centres in the brain associated with reward and motivation that could also drive food intake. Additionally, you’ll also be awake as those hunger hormones kick in, signalling that it’s time to eat again. And it’s also possible that due to impaired sleep, fatigue levels are generally higher which decreases energy expenditure during the day.

To further explore the relationship between restricted sleep and energy intake, a recent study investigated the effects of sleep extension on body weight in a group of ~80 overweight adults (41 men and 39 women). 8

The researchers noted that a lot of the previous research was conducted in a lab, and may not be an accurate reflection of a real-world setting. Additionally, the magnitude of sleep restriction was extreme in most cases.

Instead, the researchers wanted to see what would happen if they got a group of participants to improve their sleep habits, extending the amount of time they slept (versus restricting sleep).

The participants were randomised into one of two groups:

Participants needed to have been habitually sleeping less than 6.5 hrs per night and this was assessed before the trial by giving participants a wrist device (an ‘actigraph’) that assessed their sleep/wake cycle for one week. Those with sleep apnea or who were completing night/shift work were excluded from participation.

The main outcomes the researchers were interested in were:

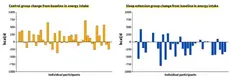

The sleep extension group also significantly decreased their energy intake compared to the habitual sleep group to the tune of ~270 kcal/day.

Between-group differences in change from baseline in energy intake: -270kcal/d (95%CI, -393 to -147 kcal/d), p<.001

Between-group differences in change from baseline in energy intake: -270kcal/d (95%CI, -393 to -147 kcal/d), p<.001

Individual participant’s change in energy intake from baseline

Individual participant’s change in energy intake from baseline

There were no differences between groups for total energy expenditure or its components.

The sleep extension group also lost significantly more weight during the experimental period (-0.48kg) compared to the habitual sleep group (+0.39kg).

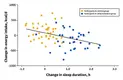

Considering all participants, the change in sleep duration was inversely correlated with the change in energy intake: For each 1-hour increase in sleep duration, energy intake decreased by approximately 162 kcal/d.

The results suggest that sleep duration likely has some role in weight management and energy intake. Where sleep is generally restricted in duration, extending sleep duration may assist in reducing energy intake and meeting weight management goals. One potential limitation to the findings of the current study is that it was conducted in a cohort of participants with overweight. It’s currently not entirely clear whether a similar effect would be observed in populations without overweight or if there is an effect, whether its magnitude would be similar to this study.

The importance of sleep likely extends beyond energy intake. Restricted sleep can impair exercise performance in some circumstances such as reaction times, accuracy, and submaximal strength and endurance. 9 10 Additionally, sleep restriction is likely to extend the time course of recovery from exercise, making it harder to recover for subsequent training sessions. 11

Overall, the science so far suggests that adequate sleep duration is important for several outcomes relevant to Physiqonomics’ readers.

What are some things you can do to improve sleep hygiene?

Exercising assists with sleep hygiene, but here are a couple of things to consider to improve sleep hygiene as outlined by Irish et al: 12

This post is taken from the Vitamin. Every Thursday, I drop some knowledge bombs on your face to help you reach your goals faster while avoiding all the bullshit.

We get so caught up in trying to find the “perfect” nutrition, training, or supplement plan that we forget some of the most effective things we can do for our health and body composition are also the simplest.

One of these things is getting enough sleep.

For starters, chronic sleep loss can have a multitude of undesirable effects on the cardiorespiratory, nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, and increase the risk of injury and illness. 1

At the broad population level, there’s an association between those with a ‘restricted’ habitual sleep pattern (less than 7hrs per night) and an increased body mass index when compared to those who have a longer habitual sleep pattern (7 hrs or greater per night). 2

There’s also emerging evidence suggesting sleep restriction causes increased energy intake.

A 2017 review reported that, compared to participants who slept ~7 hours per night, participants who slept less than 5 hours per night consumed 385 more calories per day, with more of the calories coming from an increase in fat intake. 3

Zhu et al. found sleep restriction increased subjective hunger, and the sleep-deprived participants consumed ~250 more calories per day than the participants who got enough sleep. But that wasn’t all. The sleep restriction group also gained more weight, saw a decrease in insulin sensitivity, and changes in brain activity–particularly those regions related to cognitive control and reward. 4

And more recently, a review by Fenton et al. found that sleep duration restricted to <5.5 hours per night led to a mean increase of 204kcal/d. 5

But let’s back up for a sec. Why would less sleep affect energy intake in the first place? There are several potential mechanisms, and I’ve married together the rationale from two reviews. 6 7

For starters, being awake for longer means there’s more opportunity to eat, and when you’re awake and sleep-restricted, a food stimulus has been demonstrated to enhance the activation of centres in the brain associated with reward and motivation that could also drive food intake. Additionally, you’ll also be awake as those hunger hormones kick in, signalling that it’s time to eat again. And it’s also possible that due to impaired sleep, fatigue levels are generally higher which decreases energy expenditure during the day.

To further explore the relationship between restricted sleep and energy intake, a recent study investigated the effects of sleep extension on body weight in a group of ~80 overweight adults (41 men and 39 women). 8

The researchers noted that a lot of the previous research was conducted in a lab, and may not be an accurate reflection of a real-world setting. Additionally, the magnitude of sleep restriction was extreme in most cases.

Instead, the researchers wanted to see what would happen if they got a group of participants to improve their sleep habits, extending the amount of time they slept (versus restricting sleep).

The participants were randomised into one of two groups:

Participants needed to have been habitually sleeping less than 6.5 hrs per night and this was assessed before the trial by giving participants a wrist device (an ‘actigraph’) that assessed their sleep/wake cycle for one week. Those with sleep apnea or who were completing night/shift work were excluded from participation.

The main outcomes the researchers were interested in were:

- Sleep duration using the actigraph.

- Energy intake (doubly labelled water method).

- Body composition (DXA).

- Energy expenditure (regression equations)

So, what happened?

Participants who extended their sleep successfully increased their sleep duration compared to those that stayed at their habitual sleep duration from approximately 6hrs at baseline to ~7.2 hrs (+1.2 hrs).

The sleep extension group also significantly decreased their energy intake compared to the habitual sleep group to the tune of ~270 kcal/day.

Between-group differences in change from baseline in energy intake: -270kcal/d (95%CI, -393 to -147 kcal/d), p<.001

Between-group differences in change from baseline in energy intake: -270kcal/d (95%CI, -393 to -147 kcal/d), p<.001 Individual participant’s change in energy intake from baseline

Individual participant’s change in energy intake from baselineThere were no differences between groups for total energy expenditure or its components.

The sleep extension group also lost significantly more weight during the experimental period (-0.48kg) compared to the habitual sleep group (+0.39kg).

Considering all participants, the change in sleep duration was inversely correlated with the change in energy intake: For each 1-hour increase in sleep duration, energy intake decreased by approximately 162 kcal/d.

Practical applications

The results of this month’s study found that when sleep duration was extended from ~6hrs to ~7.2 hrs, daily energy intake decreased, and body mass decreased over the study period.The results suggest that sleep duration likely has some role in weight management and energy intake. Where sleep is generally restricted in duration, extending sleep duration may assist in reducing energy intake and meeting weight management goals. One potential limitation to the findings of the current study is that it was conducted in a cohort of participants with overweight. It’s currently not entirely clear whether a similar effect would be observed in populations without overweight or if there is an effect, whether its magnitude would be similar to this study.

The importance of sleep likely extends beyond energy intake. Restricted sleep can impair exercise performance in some circumstances such as reaction times, accuracy, and submaximal strength and endurance. 9 10 Additionally, sleep restriction is likely to extend the time course of recovery from exercise, making it harder to recover for subsequent training sessions. 11

Overall, the science so far suggests that adequate sleep duration is important for several outcomes relevant to Physiqonomics’ readers.

What are some things you can do to improve sleep hygiene?

Exercising assists with sleep hygiene, but here are a couple of things to consider to improve sleep hygiene as outlined by Irish et al: 12

- Set aside ~30 mins before going to bed to be able to wind down and manage stress. Mindfulness-based strategies, such as meditation, may assist.

- Have consistent sleep/wake times.

- Decrease consumption of caffeine, nicotine, and alcohol in the hours before bed.